Wheels of Government and the Machinery of Justice in the First Capitol, The

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library Research Report Series - 0182

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library

Williamsburg, Virginia

1990

THE WHEELS OF GOVERNMENT AND THE MACHINERY OF JUSTICE IN THE FIRST CAPITOL

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation

Department of Historical Research

Williamsburg, Virginia

,

1987

THE WHEELS OF GOVERNMENT AND THE MACHINERY OF JUSTICE ON CAPITOL SQUARE

For thousands of Americans and foreign nationals who visit the reconstructed colonial Capitol in Williamsburg, the building stands as a monument to the birth of the new American nation in 1776. It was in the Hall of the Capitol where the House of Burgesses met that the future patriot leader Patrick Henry proclaimed in response to the Stamp Act of 1765, "Caesar had his Brutus, Charles the First his Cromwell, and George the Third—." Evidence suggests Henry's speech was interrupted at this point by cries of "Treason!" Upon being interrupted Henry apologized profusely and claimed that he had been carried away by the threat of the loss of liberty, but the incident is still considered by modern Americans to mark the beginning of the movement for independence in Virginia.

A second act in the drama of independence also occurred in the Capitol four years later in 1769, although this time the setting was the Council Chamber, meeting place of the upper house of the legislature and governor's advisors. Here Governor Norborne Berkeley, Lord Botetourt, dissolved the House of Burgesses for passing a series of resolves against the Townshend Acts and in support of the Massachusetts Circular Letter. The governor's statement, "Mr. Speaker, and Gentlemen of the House of Burgesses, I have heard of your Resolves, and augur ill of their Effect: You have made it my duty to dissolve you; and you are dissolved accordingly" memorialized in the now-classic film "The Story of a Patriot" seems to have been of little effect. A majority of the burgesses responded to it by leaving the Capitol and walking 2 up the street to the Raleigh Tavern. There they reconstituted themselves as an association under the chairmanship of their former speaker, Peyton Randolph, and proceeded to concentrate their energies on devising ways to prevent the enforcement of the Townshend Acts.

A final scene in the pageant of American independence took place in the Hall of the House of Burgesses in the spring of 1776 when the Fifth Virginia Convention assembled there. This gathering of patriots, including many former burgesses, drafted the resolution declaring the colonies free and independent states that was later introduced at the meeting of the Continental Congress in Philadelphia by Virginia delegate Richard Henry Lee. The Convention also produced the Virginia Declaration of Rights and the Commonwealth Constitution. The former served as a forerunner to the Bill of Rights in our Federal Constitution; the latter established provisions for the newly independent Commonwealth of Virginia. Under its provisions, the gathering promptly elected Patrick Henry first governor of the Commonwealth.

These three events, all of which occurred in the capitol, emphasize the links between Virginia's colonial government and the federal government of the United States that would evolve after it. Yet to a great extent, all three focus on the extraordinary rather than the ordinary activities which took place within the walls of the Capitol. All three center upon the actions of members of the legislative branch of Virginia government that had continued to gain strength and authority at the expense of the executive branch (the governor and his council) throughout the 18th century. Yet despite the locus of the drama of the American Revolution in the legislative and representative branch, most 3 of the business of government performed in the Capitol was carried out by appointed, not elected, public officials. Indeed, 90 percent of all Virginia's public servants were appointed rather than elected. It is with the activities of these men, performed for the most part within the Capitol, that the remainder of this article will concern itself.

In order to understand the ordinary working of government in the colonial capital, the modern reader must first understand two fundamental differences between the foundations of government in the United States as it exists today and the foundations of government in colonial Virginia. First, the non-elected officials of Virginia's provincial government, like other officials throughout the British Empire, owed their appointments to a system of patronage. Throughout the empire the chief political appointments rested in the hands of the King or his ministers. Their appointees or "clients" served at the pleasure of those who appointed them, although some appointments in Virginia were for life, contingent upon good behavior. The client often paid his "patron," the man who had appointed him, a financial remuneration in exchange for his appointment. In return, the patron benefitted from the extension of his own interest or influence by having his men in key positions scattered throughout the realm.

In colonial Virginia the governor, the secretary of the colony, members of the governor's council, the attorney general, the auditor of the royal revenues, and the receiver general all held their positions by the direct appointment of the king and his ministers. By the mid-eighteenth century most of these appointments had become so lucrative that they went to Englishmen living in England, not to resident Virginians. Each of these officials, however, possessed the right to appoint a deputy, resident in Virginia, to 4 carry out the duties of his office. Most of them did so. The deputy (or principal appointee if he lived in the colony or opted to move there) in turn held the power to appoint his subordinates. At mid-century the single provincial official holding the greatest number of such subordinate appointments was the deputy secretary of the colony, who had the right to name the clerks of all Virginia's courts. It was these resident appointed officials of the colony, usually deputies and subordinates, who were responsible for the conduct of most of the ordinary affairs of government in the colonial capital. All except the governor had offices in the Capitol and most were paid for the services they rendered through user fees; a few, however, received salaries either from the crown or from the principal official whom they served.

In addition to the fact that most governmental officials in colonial Virginia were appointed rather than elected, provincial government differed from that of the present United States in that separation of powers had not yet become an enshrined principle. Divisions between legislative, judicial, and executive authority sometimes blurred. For example, members of the governor's council served in an executive capacity when they advised the resident governor, in a judicial capacity when they sat (along with him) as judges of the highest court in the colony, and in a legislative function when they assembled as the upper house of the Virginia Assembly.

Similarly, one man might hold several different offices in provincial government. Throughout most of the 18th century, the speaker of the House of Burgesses also served as the treasurer of the colony. Sometimes plural office holding occurred as a result of the patronage system, but in this instance it was largely a consequence of an imperial policy that required the colonists to 5 finance their own government. To save money and raise the influence of the speaker, he was made treasurer as well.

The principal purpose of provincial government in Virginia was to protect the life, liberty, and property of the king's subjects residing in Great Britain who had a special interest in the colony, such as the tobacco merchants to whom Virginia planters were constantly indebted, and to protect the interests of the King himself, in his land, his revenues, and his supremacy. Nevertheless, it is with the first of these avowed goals that we shall be most concerned and which most often occupied the provincial officials housed in the Capitol. Chief among the rights that concerned provincial officials was the protection of Virginians' property. The single most significant kind of property possessed by most Virginians was land. The Capitol housed the machinery through which Virginians patented land and the records that assured them a clear title to it.

Despite the significant services of government housed there, however, not all Virginians routinely appeared at the Capitol to transact business. Slaves rarely appeared in the Capitol unless they were the objects of some criminal investigation. All free Virginians were technically eligible to conduct business in the public offices of the Capitol, but in point of fact women did not ordinarily come there. Most of the persons in evidence at the Capitol were free white males.

With the exception of criminal trials in the General Court, a great deal of the business brought before the public officials in the capitol involved a relatively small proportion of middle and upper class men: county clerks, sheriffs, and justices; vestrymen, church wardens, and ministers of the established church; lawyers, land speculators, and civil litigants 6 in the General Court; and councilors, burgesses, and other public officers doing business with officials in offices other than their own. The distance of a man's home from the capital also played a part in determining whether or not he was likely to appear in person to conduct his business. Poorer men living in Williamsburg or York or James City counties probably saw to their own affairs in person. Those living a considerable distance from Williamsburg, especially those on the frontier, frequently entrusted their business to an agent, a neighbor, often a member of the gentry, and sometimes a burgess, whose affairs regularly brought him to the capital. We know most about the routine business of government from these agents because they kept records of what was done for whom back home. Many of these documents, unlike most of the official records housed in the Capitol, have survived.

A Virginian arriving at the Capitol to do business in 1745 would have quite a different place than one arriving in 1755. The first capitol building, completed by 1705, burned in 1747. Its replacement, the second capitol, was completed in 1753. The events initiating the Revolution, discussed in the opening pages of this essay, actually took place in the second Capitol. This building fell into disrepair after the capital moved to Richmond in 1780, and it, too, finally burned in 1832. In the 1930's Colonial Williamsburg built the third building to occupy the same site. Because very little information on the architectural features and internal original arrangements of the second Capitol had survived, the reconstruction follows the original design of the first Capitol. The architectural spaces discussed below are those of the first Capitol, which correspond to those of the building which presently occupies the site. The events recounted, unless otherwise noted, 7 also occurred in the first Capitol, usually during the decade between 1737 and 1747.

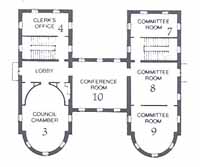

The most vital functions of provincial government in eighteenth-century Virginia were carried out in the secretary's office (room 1 on plan). Indeed, next to the governor, who had no office in the Capitol, his was the most important office in the colony. It maintained the records that insured the smooth functioning of the colony. The office contained copies of the vital statistics of Virginians including lists of births, deaths, and marriages. To insure the protection of private property, it had custody of the official volumes of land grants, and kept abstracts of all probate records. It also served as the official repository for the records of the General Court and maintained copies of numerous other kinds of documents necessary for the orderly governing of society-certificates of naturalization, lists of ordinary licenses, of passes to leave the colony, and of powers of attorney received from individuals living abroad.

The importance of the secretary's office and its lucrative income led the resident royal governors to request that the principal appointment should be held by an English-born Virginian. The first two secretaries of eighteenth-century Virginia, Edmund Jenings and William Cocke, had both been so born, but resided in Virginia where each carried out the duties of his office. By 1720 English officials had become aware of the monetary value of the office and gave it to one of their own, Thomas Tickell, professor of poetry at Oxford and the literary executor of Joseph Addison. Two years later, Tickell himself fell victim to the South Sea Bubble and sold the office to a native-born Virginian, albeit one educated in England, John Carter. Carter held the office until his death in 1742, whereupon the titular governor of Virginia, the Earl of 8 Albemarle (who never resided in Virginia) bestowed it on his private secretary William Adair. Adair likewise never came to Virginia, but appointed Thomas Nelson to act as his deputy in the colony. Both held their posts until the Revolution, and Nelson was referred to as Secretary Nelson until his death in 1787.

While Secretary Nelson had formal responsibility for overseeing the work of the office, except for the signing of a few major documents he actually performed very little of it. A bevy of clerks ranked in a hierarchy ranging from the clerk of the general court and secretary's office, Benjamin Waller, at the top to the lowliest clerk apprentices at the bottom carried on the daily affairs of the office.

The office, because of the volume and importance of its business, occupied two spaces in the Capitol. The public office was located on the North side of the West wing of the first floor of the Capitol (room 1). Ordinary access was through the doorway underneath the hyphen between the two wings, and it was probably through this door that William Cabell, land speculator and frontier bigwig, passed when he entered the secretary's office on October 25, 1744 to file the necessary certificates and pay the patent fees for 650 acres in Goochland County for himself and 400 acres for John Burks. The work space of the office was set off from the public by a wooden bar, whose top surface was wide enough to serve as a writing surface. As Cabell approached this bar, he noticed the schedule of fees prominently posted nearby.

On this particular day of October, William Wager, probably one of the junior clerks in the office, was stationed behind the bar. he accepted Cabell's certificates of survey and the necessary sums for rights and patents and drafted a receipt for them. While Wager was writing Cabell's receipt, the 9 latter's eyes wandered to the space beyond the bar. Large freestanding bookcases, many with doors, known to contemporaries as bookpresses, lined the walls; they held large folio volumes of land patent records, some containing as many as 1,000 pages each, and General Court records. Chests and trunks scattered around the room held older records which were less frequently consulted. Loose papers were being sorted or temporarily stored in pigeonholes. Canvas and linen bags were poled in one corner of the office to be used in rapidly evacuating the records in the event of fire. Of course, everywhere there were writing surfaces. These included at least one desk, which was used by the secretary himself on those special occasions when he signed documents. The room also contained several tables where clerks sat and wrote and perhaps a few standing desks which served a similar purpose. The Great Seal of Virginia, used to authenticate many documents, was kept here throughout most of the eighteenth century, although the governor was its official custodian.

The neatly dressed clerks who occupied the work space varied widely in position and authority. Wager, who wrote out Cabell's receipt, was a junior clerk, and hence in the middle rank of the clerks. Beneath him and the other junior clerks, at the bottom of the hierarchy stood the clerk apprentices. While junior clerks received salaries, clerk apprentices remained unpaid. Their lowly status in the clerical hierarchy, however, should not be taken as an indication of inferior social standing. Most clerk apprentices came from the best gentry families. They served formal apprenticeships of seven years duration. During this time their families supported them and posted bond for their performance and good conduct. They supplied the secretary's office with sufficient hands to do the voluminous copying of documents, and the youngest 10 among them also ran errands. At the end of their unpaid apprenticeships, they were rewarded with a place in the queue of graduates awaiting a vacant clerkship in the Virginia judicial system. Such a plum might bring the holder of the appointment substantial income. The fact that a county court clerk earned between £50 and £300 per annum explains why clerk apprenticeships were much sought after posts.

Wager's immediate superior in the clerical hierarchy was deputy clerk of the general court and secretary's office Thomas Everard. At this date Everard served as principal overseer of the land office and miscellaneous business of the secretary's office. Its General Court business was directly overseen by Everard's superior, Benjamin Waller, clerk of the general court and secretary's office. Waller's authority remained second only to that of Thomas Nelson, and the responsibility for day-to-day management ultimately rested on his shoulders. Waller, who had himself been a clerk apprentice, had been appointed to his position by Secretary Nelson's predecessor. He continued to serve in that capacity until the abolition of the secretary's office during the Revolution. Both Waller and Everard had served as clerk apprentices under Waller's predecessor, Matthew Kemp, and each also held a clerkship of one of the two counties adjacent to Williamsburg, Waller for James City County and Everard for York.

Because of the burdens of his position and the urgencies of General Court business, Waller probably most frequently occupied the second of the two rooms in the Capitol allocated to the secretary. The private office was in the third floor or garret of the west wing. Its furnishings were similar to those of the public office, although it was much smaller and lacked a dividing bar. Waller retired here when his more cerebral tasks required escape from the 11 hurlyburly, distractions, and interruptions of the public office. The garret office also provided a place where junior clerks and clerk apprentices could copy loose documents into bound volumes. When the first Capitol burned on the evening of January 30, 1747, several of them had been so engaged.

After the burning of the Capitol, the division of duties between Everard and Waller became even more pronounced. On May 16, 1769, when William Cabell's son William Cabell, Jr., burgess from Amherst County, delivered surveys and paid fees for rights and patents for three of his neighbors, he went not to the Capitol itself but to the free-standing and all-but fireproof Secretary's Office constructed in 1748. Everard had directed the salvage and sorting by the clerks of the Office of all the records saved from the destroyed first Capitol. Thereafter, stationed in the new building situated just Northwest of the Capitol, he assumed responsibility for records of land grants, miscellaneous records, and all non-current records of the General Court. He also oversaw the conduct of the public business of the office and served as the principal supervisor of the junior clerks and clerk apprentices.

Benjamin Waller's chief responsibility remained the ongoing records, legal processes, and procedures of the General Court. His office probably remained adjacent to the General Court Room in the second capitol, a building about whose interior spaces we know very little.

The General Court itself convened twice annually in October and April. The governor and his council sat as judges. The court possessed original and concurrent jurisdiction over all civil cases involving more than small monetary sums and before 1710 provided the only court in which free men and women could be tried for crimes punishable by loss of life or limb. In that year courts of oyer and terminer, presided over by at least five members of the council, were 12 established. They met biennially in December and June. Here any free person accused of felonious crimes would come up for trial within four months instead of every six, shortening the time that they had to be maintained in jail. Because its criminal business remained but a small fraction of its docket, in spite of this innovation, the length of General Court terms continued to increase throughout the course of the eighteenth century, stretching from eighteen days early in the century to twenty-four days, excluding Sundays, by the 1740s.

In addition to hearing both criminal and civil cases, the General Court also functioned as a court of equity. It likewise had appellate jurisdiction over every inferior court in the colony. Decisions of the General Court could only be appealed to the King and his Privy Council in London. Finally, the court served as a court of record for the colony. This fact meant that its clerk, Benjamin Waller, was responsible not only for maintaining a record of its own proceedings, but also for keeping copies of abstracts of the records from all inferior courts in Virginia. The great fullness of these records has only increased the lamentation with which twentieth-century historians view their loss in the fire accompanying the evacuation of Richmond in April 1865.

The General Court sat in a large ground floor chamber across the passage from the secretary's office in the west wing of the Capitol (room 2); it was sometimes referred to by contemporaries as the "General Court House. " The room had a raised platform in its semicircular end where the governor and at least five councilors sat upon green cloth-covered cushions. Above the judges the coat of arms of England's reigning monarch was prominently displayed. Below the judges were seats for the members of the jury, a table for the clerk and his assistants, and probably an enclosed area to contain the 13 prisoner. Space was also provided for the sheriff of York County, who served as custodian of prisoners and was in charge of the grand and petit juries, and for the crier and the tipstaff.

The members of the court and the public were separated by a bar. Illumination above the public area was provided by a glass lantern that hung from the ceiling. Light for the members of the court was provided by a large glass chandelier and glass sconces attached to the wall. By 1740 the room was embellished with a portrait of Queen Anne, which had originally hung in the council chamber above (room 3) during her reign.

In addition to maintaining a record of the proceedings of the General Court, the clerk supervised the tedious process through which General Court cases or appeals had to pass in order to be ready for the Court's attention. This was a task for which Waller, himself an able lawyer, was well suited. It was the clerk's duty, as each stage of the process was completed, to see that the next stage was completed on schedule. Periodically he held a "rule day," attended by lawyers, at which the schedule was reviewed and brought up to date. Twice a year he set the docket of cases to be heard at the following term. Thus the clerk helped to insure the orderly process of justice.

Felony cases in the General Court and the courts of Oyer and Terminer were usually prosecuted for the crown by the attorney general, Peyton Randolph. For this reason the appointee could never be a member of the Council. Like some of the other officials of provincial government, he had a private office on the third floor of the Capitol. The office contained his desk, as well as several bookpresses that held not only his own books but probably also the records of the Virginia Court of Vice Admiralty in which the attorney general usually served as sole judge. At a table in the office, the register (or 14 clerk) of the Vice Admiralty Court wrote up its proceedings. In early life, Waller held the commission as register; later on, he became its advocate or prosecuting attorney. Unlike the secretary, who relied on fees as payment for his services, the attorney general received an annual salary out of the royal revenues of the colony.

Members of the general public came into the court as jurors, witnesses, litigants, persons accused of crimes, and, of course, as onlookers. Then as now, the curious included a number of people of the more turbulent sort. All strata of Virginia society, however, were not represented equally in each of these roles. Grand jurors were chosen well ahead of scheduled sessions and notified that their presence was required. They were selected only from among men of considerable standing and reputation, although there was some attempt to see that all geographical areas of the colony were represented. Petit jurors were chosen from among those present to observe the proceedings. They were freeholders and, of course, male, but beyond those distinctions little special attention was devoted to social rank. In criminal trials at least six of the twelve petit jurors had to reside in the country where the offense had been committed.

Witnesses, since their presence was determined by some observation relevant to the case being heard, came from both sexes and all classes of free society. They did, however, receive monetary compensation for their appearance and travel expenses. In criminal cases these were paid by order of the court out of revenues raised by the colony. In civil suits the person on whose behalf the witness had appeared, either plaintiff or defendant, paid the expenses. After 1732 the testimony of slaves was not admissible as evidence against free persons in the General Court. By the 1740s slaves could give 15 evidence in cases involving crimes allegedly committed by slaves, but ordinarily such cases were heard not in the General Court, but in the localities where the offense was alleged to have been committed.

Because the records of the General Court no longer survive, modern historians possess little detailed knowledge of either the kinds of cases that it heard most often or the character of the civil litigants it attracted. Such knowledge as we do have comes primarily from records of a small number of cases appealed to the king and privy council and from information scattered in private papers. A nineteenth-century transcript (published in 1909 as Va. Col. Decisions) of two casebooks from the early 1730s suggests that most civil cases, not surprisingly, concerned questions of property and debt. Land, slaves, and the settlement of dead men's estates frequently lay at the center of such disputes. In all probability, the General Court attracted the wealthiest clients and the most difficult cases; the two were not always the same.

In 1771, when the county court of Westmoreland County decided against Councilor Robert Carter of Nomini and in favor of Thomas Edwards, who wanted to build a mill only a mile upstream from Carter's own mill, Carter promptly appealed the decision to the General Court. As one of the wealthiest men in the colony he could afford the time and expense of pursuing the case. We do not know the outcome, but Carter at least had a hearing. An order signed by Benjamin Waller and demanding that Carter pay James Bailey, one of his witnesses, 300 pounds of tobacco and nine shillings for one day's attendance at court and travelling eighty miles including ferriages survives in Carter's personal papers.

16Unlike civil cases, eighteenth-century criminal cases often involved the less fortunate members of society. There is no reason to believe that those accused of felonies and tried before the General Court were any different in this respect. Nevertheless, because of the destruction of the General Court records, the only detailed evidence concerning criminal prosecutions focuses on the crimes of the elite. The case of Lowe Jackson exemplifies this tendency.

In the 1740s Jackson, the son of a clerk of Nansemond County and a member of the gentry, was tried in the General Court and found guilty of counterfeiting. The judges sentenced him to be hanged and returned him to the Public Gaol to await his execution. In the interval, Jackson escaped from the jail and fled the colony, eventually arriving in Charleston, South Carolina. There an itinerant dancing master and painter, William Dering, recognized him and notified the Virginia authorities. The governor of Virginia sent a strong and trusted man to reclaim Jackson and return him to Williamsburg. Meanwhile, however, members of the Council, who also served as judges of the General Court, had divided over the question of whether or not he should be hanged. Jackson was, after all, beth a young man and connected to some of the best families in the province.

The president of the Council granted him a temporary reprieve from the carrying out of his sentence, while Jackson's friends and opponents, respectively, mobilized their forces. The former wrote letters to England requesting a royal pardon. Because counterfeiting was considered petit treason, only the king and not the governor of the province could pardon those convicted of it. Those opposed to showing mercy to Jackson also wrote letters to England in which they argued that despite Jackson's familial connections justice should be done and the sentence carried out. Ultimately, Jackson's 17 connections failed to save him. No royal pardon proved forthcoming, and he was hanged.

The councilors functioning in their executive and legislative modes occupied the chamber directly above the General Court Room (room 3). As the upper house of the assembly, the council had to assent to any bill before it could bacome law and had to approve any resolves of the House of Burgesses. The council was originally intended to use its legislative authority to assist the governor by preventing the passage of laws contrary to his instruction, but, in fact, because of the local orientation of its members, the council often failed to perform this duty. Together the governor and council informally heard and settled certain kinds of disputes over land claims, the location of churches and courthouses, and the conduct of Anglican ministers.

All of this business was ordinarily carried on in the Council chamber. The governor, those of his twelve councilors who came, and anyone else invited to attend their meetings, sat around a large table covered by a Turkey-work carpet. After 1722, illumination was provided by a large chandelier. Bookpresses containing legal and parliamentary reference work lined the walls. A portrait of England's current reigning monarchs also graced the wall: Queen Anne during the period immediately after the capitol was built and later, in the 1730s, George II and Queen Caroline.

Like the House of Burgesses, the council had its own clerk, who served them when they functioned in either their executive or legislative roles. The clerk of the council was appointed by the resident royal governor of the colony and served at his pleasure. During the early eighteenth century, he also served as the governor's private secretary, but after mid-century when Governor Dinwiddie introduced the practice of having his own private secretary, the clerk of the council served the governor only when he acted with the council. 18 When the council sat in its legislative mode, its clerk became entitled the clerk of the General Assembly.

With the exception of five men who served as clerk of the council under Governor William Gooch (several of whom died in rapid succession), the tenure in office of the eighteenth-century clerks of the council proved a stable one. Only three other men held it. William Robertson, a native of Great Britain whom Francis Nicholson appointed in 1702, outlived four governors and served until his death in 1739. The fifth and last of Governor Gooch's appointees, Nathaniel Walthoe, occupied his post from 1743 until 1770. He, too, served four governors and their councils. Upon his death, Walthoe, a graduate of Oxford and a barrister of the Middle Temple, was succeeded by John Blair, Jr., native-born Virginian, graduate of the College of William and Mary, also a barrister of the Middle Temple and of the General Court, and a leading member of Burgesses. Blair retained his clerkship until the beginning of the Revolution.

Walthoe, clerk of the council in the decade of the 1740s, had his own office in the Capitol located across the passage from the Council Chamber (room 4). Here he and a few assistants carried out his public duties. They issued copies of council orders to individuals who requested them, and wrote letters informing clerks and vestries of decisions of the council regarding the location of buildings. They also entered land caveats, counterclaims of individuals wishing to patent land for which another individual had already applied for a patent, and received petitions requesting permission to patent more than 400 acres of land. In Virginia such a petition was required for tracts of 400 or more acres. The clerk also drafted militia commissions and 19 prepared them to receive the governor's signature. Most of the clerk's public business was paid for by specified fees. For his ex officio services, such as letter writing and service to council, he received an annual salary; as clerk of the General Assembly, the sum he received varied according to the length of the session. The office of clerk of the council was definitely not among the more lucrative provincial offices, and after the death of William Robertson, only the two John Blairs, father and son, were able to hold both the clerkship of the council and another office of profit.

The public office of the clerk of the council was furnished in a fashion similar to that of the public office of the secretary. A bar separated members of the public arriving to conduct business from the staff who occupied the work space behind it. The room contained a desk and a table to facilitate writing, and bookpresses, chests, and trunks housed the records of the council Qating from 1680. Included among them were the executive and legislative journals of the council, rough minutes of the executive meetings of the council, and separate series of volumes for Indian relations and treaties, proclamations, and land caveats. This office, too, contained canvas bags to facilitate the evacuation of records in the event of fire, and included in a conspicuous place a list of fees payable to the clerk.

The clerk of the council also possessed his own private office or "closet" on the third floor abcve the conference room that connected the east and west wings of the Capitol (room 12). In this closet either he or his assistant drafted the fair copy of the final record of the journals of the council. The furnishings would have been similar to those of the other private offices in the garret.

20As clerk of the Council and General Assembly, Walthoe also served as the official messenger who carried legislative communications from the upper house to the lower house. In the ordinary course of carrying out such a mission, he would have proceeded downstairs to the loggia under the conference room and crossed over to the east wing. At the door to the Hall of the House of Burgesses, one of its doorkeepers granted him permission to enter. After being admitted, he delivered his message into the hands of the clerk of the House of Burgesses; then he proceeded to retrace his steps. Messages from the governor or council always came down with the clerk as messenger; communications from the burgesses to the council were always carried up by one or more burgesses.

Few historians have underestimated the significance of the House of Burgesses. Its work provided the statutory framework and fiscal authority necessary for the steady expansion of provincial government in the eighteenth century. After their election by a writ issued by the secretary's office by order of the governor, the burgesses met whenever the governor called them into session. He also had power to prorogue or dissolve them at pleasure.

The room where they gathered was less ornately furnished than the council chamber, and much more crowded (room 5). The burgesses sat on plain, backless, but cushioned benches that lined the walls and overflowed toward the center of the room. For this reason it contained no bookpresses; the records and reference materials used by the burgesses were kept by the clerk in his office. In the center of the House of Burgesses itself, however, stood a large table for the use of the clerk and his assistants and to hold the ceremonial mace of the colony. When the house was not formally in session, the mace was placed beneath the table; during official sessions it rested on the table top. 21 The one clear exception to the austerity of the hall of the burgesses was the speaker's chair. The imposing nature of the high-backed, armed chair made of walnut symbolized the authority that the speaker wielded.

Some of the most significant work of the House of Burgesses was done not at the general sessions in the hall, but in the standing committees which met in the committee rooms above it. Each of these three rooms (rooms 7, 8, and 9) was initially equipped with a table covered with a green cloth and with chairs. Since the three oldest standing committees—Proposition and Grievances, Privileges and Elections, and Public Claims—had more than a dozen members each by mid-century, the committee rooms, like the hall, had probably become quite crowded by then. They also competed for space with two newly-formed and standing committees.

In their room, the Committee of Proposition and Grievances received and evaluated petitions from individuals and propositions from county courts requesting legislative action on a variety of matters. Many of the bills that later became law originated in this committee. The Committee on Privileges and Elections provided the principal forum for discussing the parliamentary privileges and qualifications of burgesses. Finally, the Committee on Public Claims prepared the book of claims by which the General Assembly paid the expenses not covered by specific taxes. These included, among others, the pensions of superannuated public officials, compensation to disabled veterans or the widows of men killed in military service, and reimbursements to the owners of slaves executed for felonies. Much of the routine business of the house was transacted not in the hall but in these committees. Much of the writing that accompanied such business was performed by the clerks of the 22 standing committees in their closets or private offices above the conference room on the third floor (rooms 11 and 12).

Similar to the committee rooms in its furnishings and function, although much larger and more commodious, was the conference room that occupied the entire space on the second floor of the hyphen connecting the east and west wings (room 10). Here joint committees of the Council and House of Burgesses met. Ad hoc joint committees ironed out disputes over specific bills. Statutory and regularly appointed committees undertook the periodic revision of the colony's laws and drafted communications from the General Assembly to the imperial government in England. Members of both houses of the Assembly also met here for morning prayers on each day while it was in session. Because of the importance of the established church in Virginia, the furnishings of this room differed from that of the burgesses' committee rooms in one important particular: it contained prayer books for the use of both burgesses and councilors.

Because the burgesses met only sporadically, their involvement in the daily work of government and the administration of justice in the capitol was usually at secondhand. The clerk of the House of Burgesses and its speaker, who also served as treasurer of the colony, however, did continue to function even when the house was not in session.

The clerk maintained an office in the ground floor of the east wing across from the Hall of the House of Burgesses (room 6). Its furnishings were much like those of the other public offices in the Capitol and included a desk, writing surfaces for his assistants, and bookpresses, chests, and trunks to hold reference books on parliamentary proceedings and the journals of the house. Lists of fees charged by the clerk himself and by the speaker for 23 services performed for individuals were posted in a prominent place. Such services included providing copies of a particular legislative act or arranging for the passage of a private act, for example, an act for docking the entail of an estate.

The clerk was also responsible for providing copies of the journal of the House of Burgesses, and of all the acts passed in each session to the Governor to send to the imperial authorities in England, and to the council for the use of its own members. A copy of the laws of each session also had to be supplied to every inferior court in the colony. Before the establishment of a printing office in Williamsburg in 1730, the necessary copying of all journals and laws had to be done laboriously in manuscript. The clerk and his assistants may have used his private office on the third floor (room 14) above the conference room for this purpose.

The office of treasurer of the colony, although initially an appointive one in the gift of the governor, eventually came to be authorized by statute. After 1723, for reasons of economy as well as to increase the power of the speaker, the office came to be combined with that of speaker of the House of Burgesses. Thereafter, until the death of speaker John Robinson in 1766, each speaker, in turn, became treasurer of the colony. At that time the two offices were separated, but the occupants of each continued to be chosen by election in the House of Burgesses and regulated by statute.

The role of treasurer was to receive and account for funds raised through taxes to meet the expenses of the colony not covered by the standing revenues arising from the two shillings per hogshead duty on tobacco and the royal quitrents. Taxation to raise these funds took three different forms. The first was a head tax levied on all tithable in the colony and collected by 24 the sheriffs of each county. In Virginia any male over the age of sixteen and any female slave over sixteen was considered a tithable. A tax on all liquor and labor imported into the colony constituted the second form. The third encompassed any special taxes levied on an ever widening list of commodities and services—wheeled carriages, ordinary licenses, and judicial writs. Taxes in this latter category were only instituted to enable the colony to pay for its own defense in the face of the extraordinary expenses of war after 1754. The treasurer maintained an office in the third floor of the east wing (room ), but as the volume of his out of session duties increased it is likely that his clerk staffed a separate treasury office outside the Capitol for the convenience of the public.

Like the treasurer, two other revenue officers may still have had offices in the Capitol in the fourth decade of the eighteenth century, the deputy receiver general and the deputy auditor. Just as the treasurer was responsible for provincial revenues raised by newly legislated taxes, these two officials exercised a similar jurisdiction over the standing royal revenues. The receiver general oversaw both the collection of the king's revenues and the payment of the salaries of royal officials. The auditor, as the title of his office implies, audited the accounts of all transaction carried out by the receiver general and his subordinates. He also oversaw the disposition of the lands of the crown and of the revenue generated by their sale. In the first of these duties, he maintained quit rent rolls for each county. In the second, he worked very closely with the deputy clerk of the secretary's office who had responsibility for collecting the fees for writs and patents.

Both men had private offices on the third floor. Little information on the furnishings of the receiver general's office survives, but we do know that 25 earlier in the century the auditor's office contained a press consisting of multiple pigeonholes. He used it to file the documents submitted semi-annually by those of his subordinates who initially collected the revenues. Both offices contained the usual writing surfaces and materials, but their relatively inconvenient location on the third floor of the building suggests that the incumbents of all three of these fiscal offices probably maintained public offices staffed by their clerks or, as is known to be the case with the auditor, by an agent who joined this public function to his private commercial activities. The Ludwell-Blair-Prentis Store served both of the royal revenue officers and their clients in this way both before and after mid-century, and speaker and treasurer John Robinson's chief clerk built a brick office for the provincial treasury during the early 1760s.

Few records of the activities of Virginia's provincial public servants before the American Revolution survive. Nevertheless, the ordinary activities of these appointed officials and their clerks made possible the extraordinary actions that were to follow. In the eighteenth century the clerk apprenticeship system established in the secretary's office spread uniformity of legal processes and procedures throughout the colony. As the number of counties in Virginia tripled between 1700 and 1772, each new county court clerk (usually a graduate of the Secretary's office) carried his copy book of legal forms and his knowledge with him to the frontier.

Just as the county clerks carried orderly processes to the furthest reaches of the colony, the security and longevity of tenure of most provincial appointees contributed to the acceptance of centralized authority by Virginians. It also produced a cadre of capable Virginian public servants. After 1723 most clerical appointees were native-born Virginians. By the 1740s, 26 although most principal offices were held by Englishmen, the actual work was performed in the colony by their native-born deputies.

Both of these factors helped to shape the essentially conservative charactar of the Revolution in Virginia. Virginia had no Regulator movement on its frontier, and many of those who served the Commonwealth government had also served its predecessor. All three men who held the principal clerkships in provincial government—the clerk of the secretary's office and General Court, the clerk of the council, and the clerk of the House of Burgesses—moved on to hold even higher offices under the Commonwealth.

Benjamin Waller, clerk of the Secretary's office and advocate of the Court of Vice Admiralty, became sole judge of Admiralty in post-Revolutionary Virginia. John Blair, Jr., who had succeeded Nathaniel Walthoe as clerk of Council, became a judge in the Virginia General Court, and finally George Wythe, who was appointed clerk of the House of Burgesses in 1767, served as one of three judges in the High Court of Chancery, the highest court in the Commonwealth. Before his judicial appointment, Wythe also held the position of speaker in the Virginia House of Delegates, and both he and Blair served as delegates of Virginia to the Federal Convention of 1787 and of the 1788 convention in Virginia to ratify the Constitution. Washington appointed Blair to the Federal Supreme Court in 1789.

While the structures of provincial government shaped the Revolution and provided public servants for the Commonwealth, its institutional integrity did not survive beyond the colonial period. The secretary's office was abolished in 1776 as part of a revolutionary reaction against the patronage system. Its functions devolved on a variety of other agencies; for example, a separate land office was created to handle land claims and court business was handled by the 27 various courts themselves. In the process the centralized bureaucracy for training clerks was lost. Uniformity of processes and procedures declined in the early nineteenth century. Under the Commonwealth constitution, county court clerks were chosen by the justices of the county court, an even more pernicious variety of patronage than that which had been destroyed.

A separate department of the treasury was established after 1776 and, of course, the offices of receiver general and auditor of the royal revenues disappeared. The Commonwealth Constitution of 1776, continuing a trend already discernable before the Revolution, gave additional strength to the legislative branch by weakening the executive. Judges of the General Court, formerly members of the governor's council, became elected officials, but chosen by the House of Delegates in the Virginia General Assembly.

Yet despite the destruction of the institutional structure of government and its replacement with Commonwealth structures, the break with the continuities of the past was a gradual one. Even after the capital of Virginia was moved to Richmond in 1780, some men trained under the old system continued to serve, for a time, in corresponding new posts.